Another point of view

Look up. Look down. Look around.

I had the great good pleasure of speaking to a class of Pacific University MFA students last night along with writer Debbie Urbanski and my ole professor/mentor/friend Jeff Sharlet. We talked about writing the tough stuff, the emergence of civil warring and climate changing, things that can happen so slowly they’re barely detectable and then—bam!—there they are, a surrounding surprise.

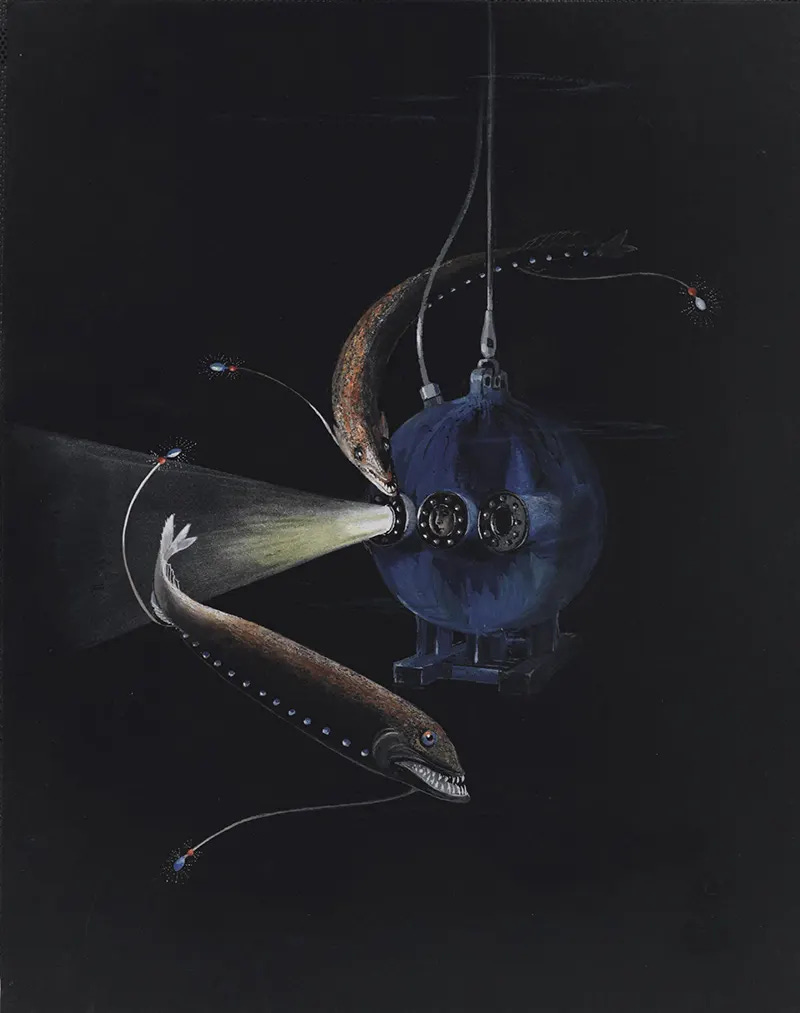

At the end, Rachael, the moderator, asked us about books that were speaking to us lately. Jeff spoke of The Bathysphere Book: Effects of the Luminous Ocean Depths by Brad Fox, which is about a 1930s expedition into the depths of the Atlantic Ocean. William Beebe (a name I know from my research on birds, but I didn’t know about his marine explorations) descended thousands of feet, secure in a 4 1/2 foot steel ball tethered to the surface, where marine biologist Gloria Hollister scribed the wonders he witnessed as he spoke through a phone line snaked through a steel cable. Jeff described the book’s section as poetic missives. I read more about the book this morning and learn of the bioluminescence, fantastical creatures, otherworldliness, that Beebe reports to his overhead colleague-scribe (and lover!) from this mysterious realm.

Before I heard Jeff’s answer, I already knew I was going to mention the novel Orbital by Samantha Harvey. What has stayed with me from this slim lyrical novel about six astronauts on the International Space Station was the joy of being granted a whole new perspective: bodies and objects that defied gravity, sure, but mostly looking through those thick windows at the green blue marble below, a growing, swirling typhoon forming over the Pacific they see again and again, as they circle the planet sixteen times in the 24-hour period that is the book. The barest blush of a plot, humans an afterthought even though they have performed the miracle of figuring out how to create a little bit of earth’s atmosphere to sustain them for months, for years. Instead, Harvey describes the twinned emotions of deep connection to the life they know is down below and the ethereal disconnect from not being able to see or feel any of it. Life below is invisible from the ISS as it hurdles above, all evidence of humans erased until lights illuminate coastlines and cities when darkness descends. And the immense breadth of the typhoon and the fires in the Amazon. Those, too, have a human fingerprint.

I read Harvey’s book as a love song to the Earth, which she calls by so many names, I began to jot them down. I read them aloud when I had the pleasure of talking to NYU’s Liberal Studies incoming class back in August, which had Orbital as its shared read. The list of descriptions that Harvey uses for this place we live includes:

This great photogenic thing, a spaceship planet, naked and startling, a hallucination, a spaceship of a planet, a buffed orb, an animal unto itself, a stately and resplendent sphere, a ball of rock, a hunk of tourmaline, no, a cantaloupe, an eye, lilac orange almond mauve white magenta bruised textured shellac-ed splendor.

The earth, she writes, it is “unearthly.”

These were the same books, Jeff’s favorite, and mine. We were both drawn to the same thing at this moment of swirling politics and weather—humans going to unearthly places to gain a whole new perspective on life on earth. Why is it that here on the surface we can get so stuck in our little lives? Everything immediate seems so grand and important. Every conflict feels insurmountable. Every effort at change immense. But imagine this: descent into the depths of the ocean tethered to the atmosphere’s oxygen above that your body needs to live and only protected from the pressure that will crush your bones by a layer of steel. Or soaring 250 miles above—more steel, more tethers—into the black ink that edges the line between our life-sustaining planet and the rest of the universe and look back down on the whole of the earth that is yours and mine and belongs to the bioluminescence and butterflies and bonobos and boletes, too. Circling it so fast (17,700 mph!) that you have 15 or 16 sunrises and sunsets in a single 24-hour period. You can't help but see things differently. How can we do this here, now?

The effervescent thinker Maria Popova, in her book The Universe in Verse, writes:

Poetry and science—individually, but especially together—are instruments for knowing the world more intimately and loving it more deeply. We need science to help us meet reality on its own terms, and we need poetry to help us broaden and deepen the terms on which we meet ourselves and each other.

Hold onto the science. Seek out the poetry.

I felt both the science and the poetry when I went to Nantucket for the first time ever last weekend to see a friend, walked the bluff among the multi-million-dollar shingled cottages of Sconcet, now mostly empty. It was not the houses that held my attention but the endless parade of monarch butterflies that were drinking up the nectar from the late season flowers that still bloomed. I'd hardly seen any butterflies this summer on the Cape, whether because of the drought or other troubling reasons I try not to think about too much, but do. They didn't show up on the milkweed that has finally established itself beside the bird bath nor in the native garden that we just planted this year. I could count the number that I saw on a single hand. But there on that island there was more than just a concentration of human wealth. There was also a concentration of wild life, drawn to the sweet nectar that would fuel the journey ahead. Those monarchs still have a long way to go. They will travel to Mexico, thousands of miles away and find the remnants of the oyamel forest where they will spend their winters, defying death and slumbering through winter before getting all sexy in the spring, living just long enough to start the next generation.

Everywhere is an island. This planet. And the hotspots upon its land, and below its waters. Last month, there was an overnight trip of the Brookline Bird Club that I really should have done. I hear the report from Mark Faherty on WCAI about their little boat out there in the waters off southeastern Massachusetts. It was an island, too. They saw the visible migration, the seemingly unseen life that is always there should we care to look or put ourselves in places where we might see it. To remind us that warblers and bats and butterflies are all flying across the dark seas under moonlight. We can check in on Birdcast and see when the peak migrations are underway, so much feathered mass in flight that they trigger radar, but we can also think about that one butterfly. That single monarch that weighs less than a penny. This one in the picture above, his wings so translucent that the flowers’ shadow shows right through them. (Yes, it’s a male. See those two little dots?) Those wings that will have the power to carry this one little life from Massachusetts to Michoacán in a matter of weeks, its view changing by the day as it travels, looking down, looking up, looking forward, looking beyond.

Might we do the same?

Journalists & writer friends, take note…

Orion magazine’s submission window is open! Now accepting nonfiction story pitches for its Summer 2026 Whale Issue: The Deep Dive. Deadline: Oct. 15

Upcoming…

Writing the Personal and the Planetary: Join me in conversation with Orion publisher Neal Thompson for a virtual discussion about writing at the intersection of nature and culture. What are some ways writers can approach environment and climate change, in both the personal and planetary sense? What are some strategies to conduct research and interviews given the volatile political landscape, from the local level to the global? How can writers navigate the publishing landscape as support for the arts, humanities, and journalism continues to shrink? This free hour-long conversation on Oct. 22nd at 6pm (ET) will also include time for audience Q&A. Register for this free event here.

I’m excited to share that this year I’ll be part of an amazing cohort of folks privileged to be part of a brand new endeavor at Boston University. The Environmental Justice Community Impact Fellowship (CIF) is an eight-month program sponsored by The Center on Media Innovation & Social Impact at BU’s College of Communication. CIF supports New England-based activists, organizers, artists, and visionaries working to strengthen climate resilience and promote environmental justice in their communities. I’m joined by other fellows: founding pastor at New Roots AME Church Rev. Mariama White-Hammond, environmental analysis and policy student Jaelyn Carr, Pulitzer Center reporting fellow Barbara Espinosa Barrera, photojournalist Julia Cumes,

community engagement manager at the Boston Food Forest and co-founder of EquiTable Mark Araujo, and Data+Soul researcher Bobbie Norman. I can’t wait to learn from all these talented people. For those in the Boston area, please do join me and other journalists, scientists, activists and artists on November 7 for the MISI Summit: Communicating Climate. Register for free here.

I’m reading…

Among the Ruins in Broadcast, another achingly beautiful piece on mothering against the “apocalypse” by Emily Raboteau

North to the Future: An Offline Adventure through the Changing Wilds of Alaska by Ben Weissenbach, an impressive first book for someone just out of undergrad, where he was one of my students when I was a visiting prof at Princeton. I take zero credit. He had John McPhee as a prof! :)

Bill McKibben’s Here Comes the Sun about the utter transformation of our global energy system that no one is talking about. (Also check out his conversation with David Roberts and Jamie Henn on the Volts podcast.)

Impasse: Climate Change and the Limits of Progress by Roy Scranton’s new book and also his new essay Strange New World in Emergence, about the Indiana Dunes, nature writing, and metaphysics.

SSM (shameless self-promotion)…

Yes, of course you can pre-order A BETTER WORLD IS POSSIBLE

Global Youth Confront the Climate Crisis. In anticipation of the March 3, 2026 pub date, do send along any suggestions for book festival organizers, reviewers, educators, librarians, and the like who might like to get an advance copy.

Coda…

Elephants, we have finally learned, have names for each other. This photo I snapped in Kenya back in 2010, a wondrous moment, to be present among the ancients and the young. What might these two call each other?

Meera such good things to ponder . Thanks !!