“Let’s talk about mushrooms. That’s a really good story. I love the mushroom story.”

That was Margaret Atwood’s response to Ezra Klein when he asked her about what what is not being discussed, but should be. Something fundamental. (Go to 1:03:30 here to listen.) I suspect he was expecting a response a little more on-the-nose about authoritarianism, but Margaret’s right. Mushrooms utterly break down hierarchies, and categorization, along with biomass. Spend any time considering the mushroom and you will have your mind blown, no ingestion necessary.

The latest issue of Orion magazine is all about fungi. It includes pieces from some of my favorite writers: Maria Popova, Erica Berry, Eula Biss, and Lia Purpura. There’s a conversation between Merlin Sheldrake, Jeff VanderMeer, Kaitlin Smith and Corey Pressman. And so much more! I encourage you to subscribe to Orion if you don’t already. It’s a beautiful, nonprofit, ad-free magazine about nature and culture that, in print, is an absolute pleasure to hold.

I had the honor of writing a piece, too. The Food & Environment Reporting Network helped fund the story “Out of the Ashes,” (thank you!), which considers the future of fungi (and us) in a warming world. I was drawn to the stories of Christian Schwarz and Ron Hamill, of their encounters with fungi and fire, of discovering newly named “exuberant cindercaps” but also watching mushroom flushes that felt like last hurrahs. Their stories make up the piece. But, honestly, one of the hardest parts about reporting is that so much never makes it into the story, but still informs me in so many ways. People are so generous with their time, with their experiences, their knowledge. Pages of notebooks filled. Tape running. And then it sits in my files forevermore. Please go read the final story, but I thought I’d use this space to share some of the outtakes:

Return to Oregon

I was able to get back out to my old stomping grounds in Oregon at peak mushroom season to do reporting. Or, rather, what should have been peak mushroom season. It’s late October but it’s dry. Too dry. I took a mushroom identification class back in 1996 or so with Joe Spivack, and he proved a generous guide for this story. I stay with him and his wife, who are both good friends of mine. They have a weather station perched on their deck, the monitor affixed to their kitchen cabinets. The rain what was supposed to come that week registered a pathetic .1”.

We slip in a mushroom hunt on our way to the coast for the Yachats Mushroom Festival on the coast, bumping two miles up a logging road into the Cummins Creek Wilderness. The air of the forest is intoxicating. Cathy points out European buttercup, an invasive, that covers the ground, but also elderberry, sorrel, nettle. Names of plants I once knew come back to me. Western hemlock. Spruce. A few Douglas firs. Many of these species have close associations with mushrooms. We find a boletus, a false chanterelle, a short-stemmed russula, clavilina corral mushroom, Inocybe, a pile of Suilus, and Agaricus subrutilescens, which is good eating, the first find worth saving after twenty minutes of mushroom hunting. But Joe sees what’s not there. The mushrooms that are missing.

Finally we work our way up a steep hill to get off the trail and deeper into the forest, and almost immediately, Cathy finds chanterelles buried beneath sword ferns so immense they wrap our waists and disappear our legs. We lean down. We look. We ready our knives. Joe explains they’re slow-growing, and probably came up with the rains that were “normal and good” in September. We eventually get a few pounds among us, cleaning them off as we put them in our baskets and bags. “We should find like 60 species up here. We’ve found—what?—maybe nine, ten?” he yells to the trees as much as to me and Cathy. “This place is fungally devoid!” which makes me smile, even though there’s a pit in my stomach when you see these indicators of a changing ecosystem.

We leave with our small haul, winding the rest of the way on 101 into Yachats, crossing the Yachats River where bald eagles soar and seals frolic in the waves that pound the beach.

We never stop moving

It’s 9:15 in the morning and there’s still a chill in the air when Joe and I pull up into a parking lot at the Oregon Dunes Natural Resource Area. We’re met by Frankie, a black dachshund-pit bull mix whose human is forager and chef Joseph Crawford. I’m tagging along with him, Trent and Kristen Blizzard of Modern Forager, and their friend Jeem, everyone loaded up with gathering baskets, bags, knives, paintbrushes, and walkie-talkies. Water and sandwiches are already stashed in backpacks and the Gaia app set into motion. We walk across the parking lot, into the sand towards the edge of the shore pines—about 90 seconds of movement—before Trent cries out, “Matsi!”

For the next six hours straight we move, sometimes together, sometimes spread out, always within a holler of each other, or a two-note whoop that Kristen has for her husband, or resorting to the walkie-talkies when the distance gets too far. When it’s time to eat, Joseph pulls a sandwich out and takes a bite…and continues to move. There are logs to sit on. We do not sit on them. Instead it’s burritos al camino and sips of water sucked from Camelbaks.

We pass through a forest, spy bear prints that look quite fresh, cross a highway of sand dodging ATVs that appear suddenly. The dunes curve, the forest changes, from shore pines to pokey spruce forests that look like a fairyland of green amid a desert. Each ecosystem a world unto itself. There we—meaning the pros—find King boletes, Boletus edulis. We duck under the boughs of spruce, step through salal and kinickkinnick with bright red berries. The ground is spongy underfoot. We want to lie on it, sleep on it. I want to lie on it, sleep on it. But no, we keep moving! Trent is off ahead, nearly out of range, and Kristen checks in on him on channel 2 every once in a while. He sees a what we learn later is a ruffed grouse that seems to be following him. I think it’s my spirit animal, he says over the walkie talkie. The bird comes to me and Kristen. Keeps following our group, in spite of Frankie chasing it, causing it to fly into the low branches of spruce. Joseph is in awe. Tells me later, if I was alone, I would have stayed for an hour with it, meditated with it. He is wonderstruck. We all are.

In one rare moment, our group of six stops moving, Joseph and I grazing on an evergreen huckleberry bush festooned with dark purple berries that pop in our mouths. We talk about what is known about fungi. Frankie is grazing on the lower branches, lapping off the berries with his tongue.

“The black trumpets that grow here in Willamette Valley show up in random-ass places,” Joseph says. He is less interested in what we know and wants to revel in the mystery. “I’m trying to say we have no fucking idea why something grows there… There’s something super complicated and super confusing about fungi.” And that’s the beauty.

Hours into our journey, I learn to see. It brings me to my knees, which sink into the sand. I reach for my knife. I cannot see the matsutake mushroom, but I know it is there. The dark asparagus-like stalk of a late-stage candystick/candy cane/sugarstick, Allotropa virgata, is a giveaway, since the parasite cannot live unless it thieves carbon from the green plants, those sun drinkers, around it, using the hidden underground threads of matsutake mycelium as the energy conduit.

A foot away from the candy cane is a hump pushing up the duff of the forest floor an earthly eruption. This is puhpowee, visible. I dig the point of the knife down around the stem as far as I can, as I’ve watched the experienced mushroom hunters I’ve been with for hours do repeatedly. I unearth a perfect 8” mushroom. My companions, whose bags are already laden with matsutakes and boletes, share the joy. I have found my fungi lens in these coastal Oregon dune forests.

Jeem hands me the cheap paintbrush we’re using to brush the sand off the bulbous base of the stalk, revealing creamy white. Before tucking it into my sack, I bring it to my nose to breathe its singular smell, piquant and woody, and that evening, I breathe in the scent again when I slice the firm flesh into thin slices and drop them into ramen broth. I take it into my body. The satisfaction of finding one’s food, plucking it alive from the earth. When I ask Kristen, “Why mushrooms?” she tells me it’s all about the community. She can open a bottle of preserved mushrooms and memories flood back of the day they were picked, the friends she was with. “So much of the terroir, that you recall with that smell.”

“I mean ‘looking’ not just in the sense of ‘seeing’ but also ‘looking for,’ to seek without the certainty of finding,” wrote Maria Pinto. “It is a kind of humble attention to the world, using all your senses to open yourself to life and the land.”

Mycologists, next gen.

Susie Holmes has been teaching biology at Lane Community College for 16 years, including mycology. Every year, she takes her students out to the forest that cradles the campus in south Eugene. “It's a wonderful stand of oak and conifer,” she told me as we sat on strawbales at the Mt. Pisgah Arboretum the day before its mushroom festival. “So a nice set of ectomycorrhizal hosts.” She sends the student out to specific areas to document every single species of mushroom they can find. What is the species richness? Observe everything. Count how many individuals there are, the species abundance. Pay close attention. (This is why I love scientists. And poets. They spend their lives mastering the art of paying attention.) What happens when the adjacent stand is clearcut? The next year, the mushrooms were silent. She showed me a spreadsheet “We identified 397 distinct taxa over 15 years. 334 species.” Abundance. Richness. She teaches at college, but also volunteered at both mushroom festivals I attended. Sparking the next generation, and the one after that, with knowledge.

“We’ll find out.”

By the end of my reporting, I realize I am thinking more about how fungi are changing in a time of climate crisis, which is the direction the story eventually went. Also at the Mt. Pisgah mushroom festival, I sat down with Noah Siegel, who just published a field guide, Mushrooms of Cascadia, with Christian Schwarz, who leads my story. Noah calls himself @mycohobo on Insta, spends months on the road following fungi. He can identify just about anything, and he’s seeing changes. Go into the southern Sierra Nevadas in California, he tells me, and you’ll see it. A third of the trees, dead from the last drought. Over the last handful of years, he’s seen the treeline literally going up in elevation.

“On the north coast of California, southern coast of Oregon, you can really notice the stress in the Sitka spruce,” he says. Summers have 35% less fog than they used to. And the trees need cold, wet summers. Without it, needles tumble off. Trees die back. “It wouldn't surprise me if that tree disappears from California in the next 50 or 75 years.”

As for mushrooms in those conditions, “You just don't find anything,” he says, too dry and then, all too quickly, too cold. “I mean, that's happened a lot lately.”

“How long can that happen before the system…?” my question drifts off.

“…Collapses?” Noah fills the space. “We'll find out.”

But, he’s not too dire. “You know, all these things have survived far worse droughts than what we've experienced lately. And they've also survived through ice ages. I mean, they're resilient. It just may be different from what we're used to.”

You need a wild forest

I meet Molly Widmer a week before she is to retire from her life of work as a BLM botanist. Her fair skin is brushed with freckles and her body can barely contain the energy of someone, it seems to me, who should be entering the work force, not leaving it. She tells me she likes to remind obsessive mushroomers of the ecosystems that are needed to provide for the delights they gather.

“Do you like chanterelles, boletes, matsutake, russulas?” she asks them. “You cannot have them without a wild forest.”

Yes, you can cultivate some mushrooms, but the vast majority need conditions we can barely understand. A certain plant, this much rain, that much cold.

“Mushrooming,” she says, “lends humility. There they are! There they aren't! When will they be back? We have no idea.” No fucking idea.

Here’s to humility, and all the wild forests and rank places that bring us the bounty we need to survive and delight in the world.

Journalists & writer friends, take note…

The Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources, in partnership with the Uproot Project, is offering Reporting on the Urban Environment, an expenses-paid workshop for journalists of color. Deadline: June 6

Grants of $5,000 to $10,000 available to support significant reporting efforts that lead to the publication of content connected to the Colorado River Basin from the Water Desk, based at the University of Colorado Boulder. Open to journalists (freelance and staff) and media outlets. Deadline: June 16

And from the Department of Good News…

Scientists at the Alhambra, the thirteenth century Moorish palace, in southern Spain, are ensuring that the grounds preserve biodiversity along with human history, reintroducing lost species and managing to create habitat. Newt sex!

I’m reading/listening…

…to so much goodness!

Martha Park, who was one of our Religion & Environment Story Project fellows, has published her first book, World Without End: Essays on Apocalypse and After. A beautiful inquiry into motherhood, faith, and how to live in the world, written through memoir and reported essays. We had a lovely conversation about it that will be published soon.

Listen (or read) Annabel Howard’s piece Thirty Years in Emergence. I enjoyed listening to her read it in her lush voice.

Spy on Devon Frederickson’s life in Norway via Instagram as she works on her new book about the community of people who coexist with common eider ducks.

Corey Farrenkopf was the librarian at my local library until he shifted farther out on the Cape. He’s been a dogged writer, and and his new collection of short stories, Haunted Ecologies, brings together eco themes and horror, a genre I haven’t read since I binged on Stephen King as a teen. Really, these days, they’re not so far apart. He also has a novel. Go, Corey!

Just finished Via Negativa by Daniel Hornsby, whom I’ll have the pleasure of teaching with in Sewanee School of Letters this summer. It’s about a priest on the run, moving both away from and towards something as he tries to find some sort of peace, an injured coyote as companion. Full of thoughtful luminous lines like, “I felt that a blanket of darkness had been pulled over things. Or a blanket of false light had been stripped away….”

I’m calibrating my consumption of news, and appreciating Trump’s environmental policies quantified by Jeff Tollefson in Nature.

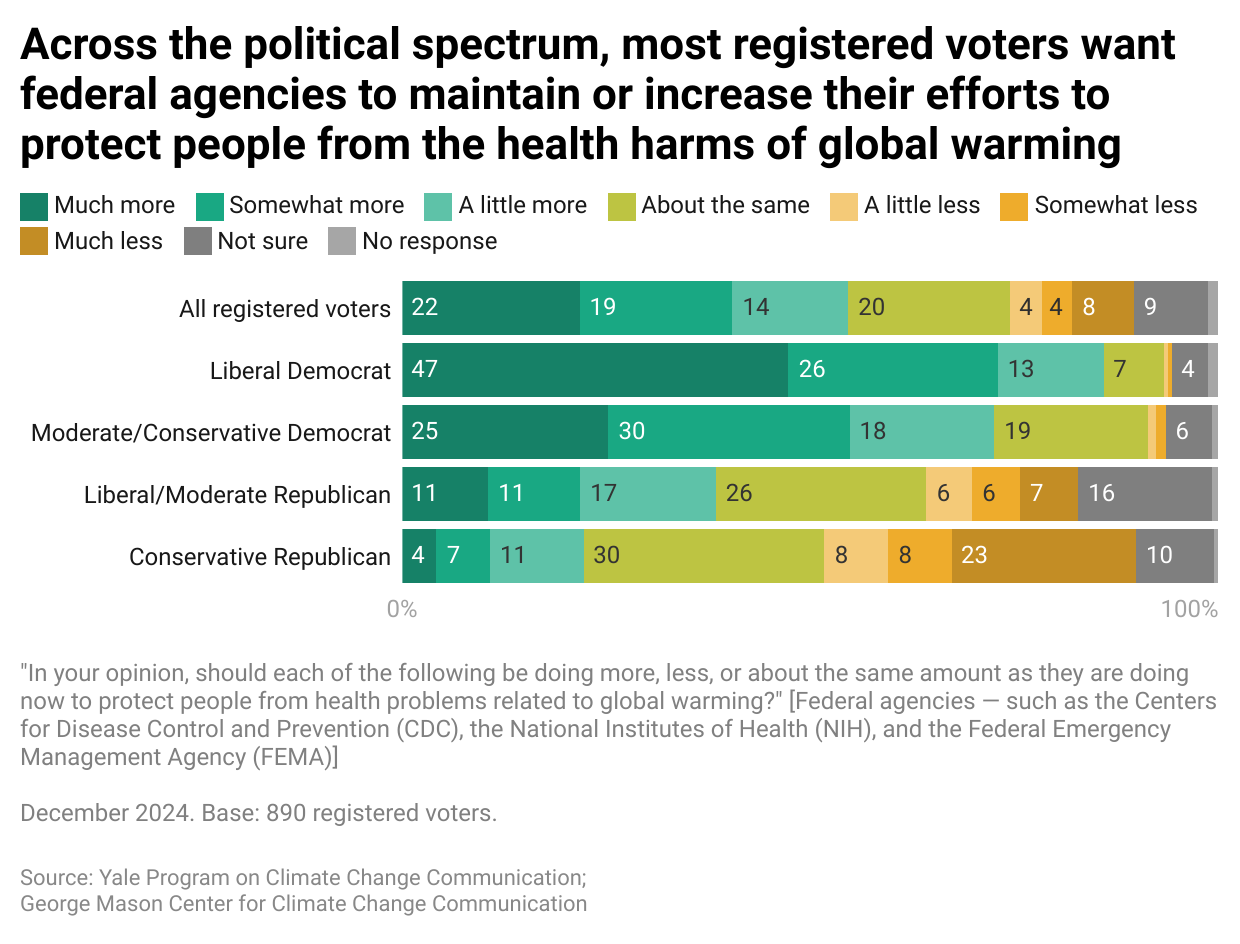

Climate Note, a new report from the great researchers at the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication shows that “ a majority of registered voters want federal agencies to increase their efforts to protect people from the health harms of global warming.”

And then check out the women making their dream maps in India, showing how they envision restoration of once communal lands.

Coda…

I am still highly distracted by the turkeys that are in the yard continuously. More pulling down books on birds from my bookshelves. More realizations. We live in a lek! An exploded lek! (Not so different than the sage grouse ones that draw tourists from far-flung places out west.) Most of the females have disappeared, presumably to sit on nests, and it’s primarily down to three males vying for the affection of a single female. One fellow is in the lead. There’s been some more fighting among two of the boys (the third hovered longingly, “Doesn’t any one wanna fight me?”), but mostly strutting. So. Much. Strutting. If I were a filmmaker, I’d direct a scene where a woman is quietly eating her dinner with focus while three men flex their muscles and pump their chests behind her. And she pays them no attention at all. But she’ll make her choice, eventually. She seemed close yesterday, letting the lead circle around her like a planet around a sun. And this morning the yard is quiet. Except for the brood of hairy woodpeckers chittering and chirping from the hole in the tree visible from my desk. Heading to Sewanee, Tennessee to teach in a few days. Hoping for woodpecker fledging to witness before I depart, and that the turkeys don’t move in with S. in my absence. They’re getting very very comfortable…

Puhpowee❣️